Personal Information

|

||

|

Name

|

Arnold Josef Rose

|

|

| Gender | ♂️ Male | |

| Died | 25-08-1946 | London |

Spouses ( 1 )

|

Spouse

|

Justine (Ernestine) Rose-Mahler | |

| Children |

♀️ Alma Maria Rose

♂️ Alfred Eduard Rose |

|

Events

📍 London

Additional Information

|

Additional Info

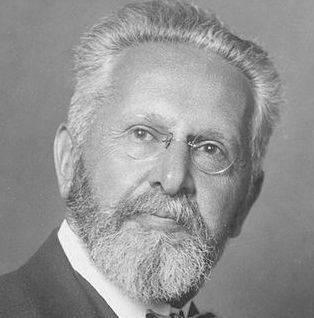

Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946) (1923). Relation to Gustav Mahler (1860-1911): A brother in law.

More

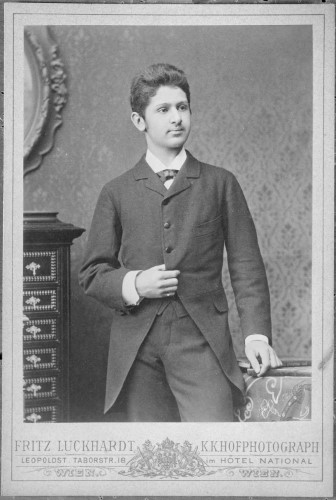

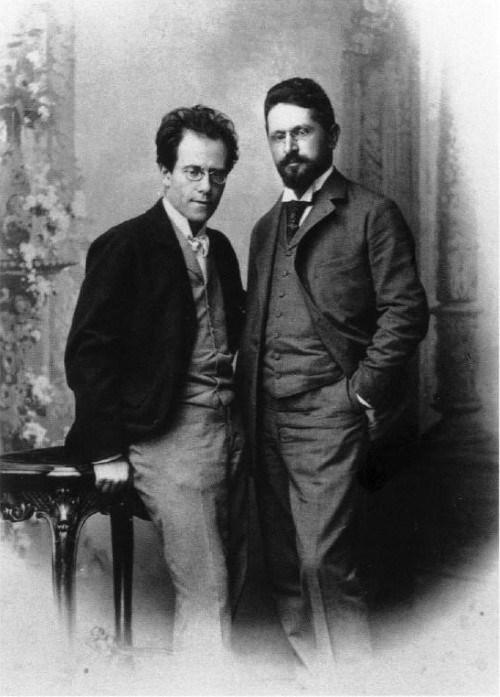

Year 1887. Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946). Year 1894. 12-11-1894 Handwritten honour (#7371) from Franz Josef I, Emperor (1830-1916) of Austria, granting Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946) the title "K. und K. Kammer-Virtuosen." Year 1894. 12-11-1894 Handwritten honour (#7371) from Franz Josef I, Emperor (1830-1916) of Austria, granting Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946) the title "K. und K. Kammer-Virtuosen." Year 1899. Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) and Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946).

Year 1899. Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) and Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946). 1923. Vienna 24-10-1923. Letter from the Mayor of Vienna (signed), on official letterhead, congratulating Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946) on his 60th birthday, and elevating him to the status of a "Bürger der Stadt Wien".

Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946). Rose Quartet.

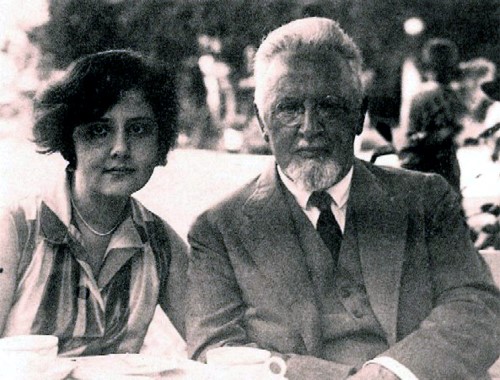

1927. Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944) and Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946).

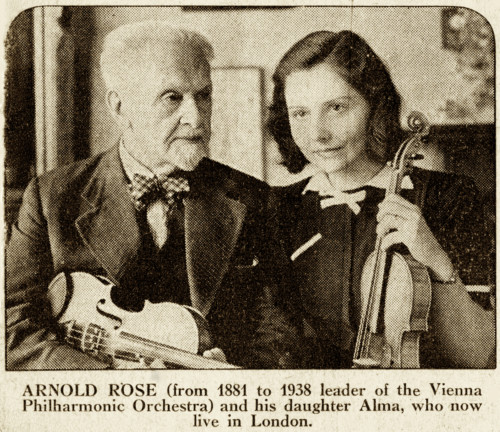

Ca. 1939. Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946) and Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944) in London. Adrian Boult (1889-1983) and Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946). Wilhelm Furtwangler (1886-1954) and Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946). Lotte Lehmann (1888-1976) and Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946). Alfred Muzzarelli, Estherhazy, Lotte Lehmann (1888-1976) and Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946). Arturo Toscanini (1867-1957) and Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946). Arturo Toscanini (1867-1957) and Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946). Arturo Toscanini (1867-1957), Lotte Lehmann (1888-1976) and Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946). Richard Strauss (1864-1949) and Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946). 1938. Vienna Richard Strauss (1864-1949) and Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946). Before the 'anschluss'. Grave Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946). Grinzing cemetery (20-5-6), Vienna, Austria. Grave Arnold Josef Rose (1863-1946). Grinzing cemetery (20-5-6), Vienna, Austria. Arnold Josef Rosé (Rose) was a Romanian-born Austrian Jewish violinist. He was leader of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra for over half a century. He worked closely with Brahms. Gustav Mahler was his brother-in-law. Although not known internationally as a soloist he was a great orchestral leader (concertmaster) and player of chamber music, leading the famous Rosé Quartet for several decades. Arnold Rosé was born in Ia?i (Jassy) in what is now Romania. As he and his three brothers showed musical potential the family moved to Vienna, where his father established a thriving business as a carriage builder. Arnold began his musical studies at the age of seven, and at ten entered the first class in violin at the Vienna Conservatory, receiving instruction from Karl Heissler. He made his first appearance in 1879 at a Leipzig Gewandhaus concert, and on 10 April 1881 appeared with the Vienna Philharmonic in the first Viennese performance of Goldmark's violin concerto under Hans Richter. Shortly thereafter he was engaged as solo violinist and leader of the orchestra at the Hoftheater, or Vienna Court Opera (later the Staatsoper). This orchestra, in unique Viennese tradition, played both in the orchestra pit and on the concert platform, and later became known as the Vienna Philharmonic. He remained leader of these two venerable institutions until the 1930s. His reputation as an orchestral leader became legendary. For Sir Adrian Boult, he was quite simply “Europe’s greatest orchestral leader of his time”. In May 1936, he conducted the VPO Beethoven's Ruinen von Athen overture as the filler side of the three-sided recording of the Leonore Overture No. 3 conducted by Bruno Walter and released on HMV/Gramophone/Gramola/Victor 78s; both performances were both interpreted and played magnificently, as were many other VPO recordings of the period just before the 1938 Anschluss, most notably Walter's equally monumental 1936 readings of Beethoven's Pastoral and Schubert's Unfinished symphonies. In 1882 he founded the famous Rosé Quartet, regarded as the finest string quartet of its time. The other members were Hummer (2nd violin), Sigismund Bachrich (viola) and Lohse (cello). From 1893 to 1901 Rosé taught at the Vienna conservatory; he rejoined the faculty in 1908 and stayed until 1924. In 1888 Rosé made successful tours through Romania and Germany, and in 1889 was appointed concertmaster at the Bayreuth Festivals. The story is told that during a performance of Wagner’s Die Walküre the orchestra was losing its way and on the verge of breaking down. Rosé stood up and gave a confident lead, bringing the orchestra back together and in tempo. Mahler, who was in the audience, is said to have exclaimed: “Now there IS a concertmaster!” Both Arnold and his brother Eduard, the cellist, were to marry sisters of Mahler. Mahler moved from Hamburg to Vienna in 1897 to become director of the Vienna Hofoper (later Staatsoper). His sisters Justine and Emma joined him in Vienna a year later. Eduard married Emma that very same month. Justine continued to live with her brother Gustav, keeping house for him. It was not long before a romantic attachment formed between her and Arnold. But it was kept a secret, Justine being unwilling to marry until her brother had found himself a wife. This happened in 1902 when Gustav married Alma Schindler, nearly 20 years his junior. She was considered “the most beautiful girl in Vienna”, and was the daughter of the landscape artist Emil Jakob Schindler. They were married on 9 March 1902, and Arnold and Justine were married the next day. The Rosé family lived in comfortable circumstances, but life was never easy for Jews anywhere in Europe. Emperor Franz Josef had guaranteed “freedom of religion and conscience” in 1867, but the reality was often different. They had two children, Alfred Eduard Rose (1902-1975), who became a pianist and conductor; and Alma Maria Rose (1906-1944) who was a very successful violinist, but whose career took a highly tragic turn as she ended up directing an orchestra of prisoners in the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp and eventually died there. Justine Rosé died on 22 August 1938. Arnold was devastated by her death. Unable to continue living under Nazi occupation, he left Vienna four weeks later and travelled via the Netherlands to England, where he spent the last six years of his life. He continued to play chamber music with Buxbaum and other colleagues. His last appearances were in 1945, so his career stretched over 65 years. After he learned the terrible news of Alma's death at Birkenau, he found it difficult to continue with his work and died soon afterward. He published editions of the violin sonatas of Bach and Beethoven, and of Beethoven’s six early Quartets Op 18. In January, 1946, the Vienna Philharmonic "wished to reinstate" Rosé as concertmaster but he refused, saying in February that "56 Nazis remained in the Vienna Philharmonic" an estimate his son believed to be far too high, but now known to be close to the actual number of fifty (sixty had been members during World War II, and after the Allied victory, the orchestra expelled ten members for their Nazi activities). Rosé received the Grosse Goldene Verdienstkreuz from King Ludwig II of Bavaria. On the occasion of his 60th birthday he received the honorary title of “Hofrat” (Court Counsellor) which was a professional rank above “Professor”. He received numerous other awards from the Habsburg, Spanish and Italian courts, the republic of Austria, and the city of Vienna. He was a member of the royal musical establishment with the rank of k.u.k.Hofmusiker (Royal and Imperial Court Musician), and as such he had the privilege of a court carriage to carry him to the opera. He also had his own carriage, with fine livery, which took him to concerts at other venues. More The name Arnold Rosé still conjures up a vision of the last days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and a legendary period in the history of the world’s greatest orchestra, the Vienna Philharmonic. One of Central Europe’s most characteristic violin virtuosi, Rosé was at the centre of musical life in Vienna for more than half a century and it took the Anschluss of 1938 and the advent of Hitler’s henchmen to shift him. His destiny was intimately bound up with the two most dynamic and controversial men in Viennese music at the turn of the century, Gustav Mahler and Arnold Schoenberg; and he represented the final glory of the nineteenth-century Viennese string style which Fritz Kreisler, a crucial 12 years his younger, was soon to overthrow. He was born Arnold Josef Rosenblum in Iasi, Romania, on 24 October 1863 and studied under Carl Heissler at the Vienna Conservatory, graduating in 1879. A wealthy stockbroker and amateur fiddler offered to sponsor a course with Joseph Massart at the Paris Conservatoire but when Rosé auditioned for the Belgian master, he was dismayed to be told: ‘You play the violin very well, but your playing is like a beautiful flower without perfume.’ Through his tears, the 15-year-old told Massart he would not take lessons from him at any price. Dispensing with further instruction, he made his début at the Leipzig Gewandhaus on 30 October 1879, with Carl Reinecke conducting, and embarked on his career. On 10 April 1881 he played the Goldmark Concerto in Vienna with the Philharmonic under Hans Richter and was immediately appointed by Wilhelm Jahn, director of the Court (later State) Opera, to the post of deputy concertmaster and first soloist. The following year Rosé founded his quartet, which was considered not least by Brahms an advance on Hellmesberger’s. By 1884, when he gave his first Viennese performance of the Beethoven Concerto (under Richter), he was senior leader of the orchestra both in the pit and when it appeared in concert as the Philharmonic; and from 1888-96 he led the Bayreuth Festival Orchestra. He had a fruitful collaboration with the ageing Brahms: on 22 February 1890, with Reinhold Hummer as cellist and Brahms at the piano, he introduced the revised version of the B major Trio, Op. 8, to Vienna; and with his quartet, he gave the local premières of the G major Quintet that same year and the Clarinet Quintet in 1892. Rosé joined the Vienna Conservatory staff in 1893 and taught there until 1924 (by which time it was the Academy of Music) but had no great success as a pedagogue, although many of his pupils made excellent orchestral players. His place in the musical establishment was fixed when he wed Mahler’s sister Justine in 1902 his elder brother Eduard (1855-1942), a cellist, was already married to the composer’s youngest sister Emma. For a number of years he was Bruno Walter’s sonata partner, taking part in the premières of the conductor’s own Sonata and Trio, the latter with the cellist Friedrich Buxbaum. These three also introduced Erich Korngold’s Op. 1, the D major Trio. Fittingly, Rosé’s musical farewell to Vienna came when he led the Philharmonic in Mahler’s Ninth Symphony under Walter’s baton, on 16 January 1938. Desolated by his wife’s death and the Anschluss, he found himself unceremoniously pensioned off by the Nazis and virtually penniless, as his savings had evaporated with inflation. Carl Flesch got up a subscription for him and in 1939 he settled in London. He celebrated his 77th birthday by playing Beethoven’s Sonata Op. 12, No. 3 and Brahms’s Trio Op. 8 with Myra Hess and his fellow exile Buxbaum in a National Gallery concert; and this line-up repeated the Brahms performance for his 80th birthday concert at the Wigmore Hall. He died at Blackheath on 25 August 1946, having recently had confirmation that his daughter Alma, also a violinist, had perished at Auschwitz. For his memorial concert at Chelsea Town Hall in 1947, Bruno Walter played the piano, Margarete Krauss and Paul Schöffler sang and Buxbaum joined the Blech Quartet in Schubert’s C major Quintet. As a soloist, Rosé played contemporary composers as well as the classics he presented Goldmark’s Concerto several times, Sir Alexander Mackenzie’s in 1886 and Stefan Stocker’s in 1888. He performed Reger’s C major and F sharp minor Sonatas, the F major and A minor Suites and E minor Trio with the composer at the piano. He premièred Gustav Hawranek’s A major Sonata with Franz Schmidt at the piano, and Ignaz Brüll’s Sonata with the composer. He cried off giving the first performance of Webern’s Four Pieces, Op. 7, but later played them with the composer. Even in the late 1930s he was eager to perform Berg’s new Concerto. Rosé was a scintillating soloist in his prime, as records made from 1900 to 1910 testify most are cut to fit the confines of a single 78 rpm side but they give good snapshots of his playing. He had a fluid technique and though he was not above making ‘improvements’ to the music he played, they were usually in good taste. Of these early records, perhaps Ernst’s Fantasy on Rossini’s Otello is the finest: Rosé ‘sings’ the tragic Desdemona’s beautiful song in perfect bel canto style, with fine tone, and manages the trickier episodes masterfully. Sarasate’s Faust Fantasy is also particularly fine. His sonorous G string tone can be heard on a 1928 record of Bach’s Air in Wilhelmj’s quartet arrangement. The Adagio from Bach’s G minor Sonata, Rosé’s only electrical solo record, delivers his tone with fidelity but finds him phrasing a shade more stiffly than of yore and with his previous impeccable intonation under threat from old age (this side was made on the same day as the famous 1929 Bach Double Concerto, with daughter Alma playing the other violin and son Alfred conducting a chamber orchestra drawn from the Philharmonic). Incidentally, it is fascinating to note that Arnold Rosé’s performance of Bach’s E major Concerto on 16 November 1884, with Richter conducting, was the first ever given in Vienna. Today Rosé is usually remembered for his leadership of the Vienna Philharmonic, a role in which he worked closely with such conductors as Richter, Strauss, Mahler, Toscanini. Schalk, Weingartner, Krauss, Knappertsbusch and Furtwängler. In both concert hall and opera pit, he took part in the premières of many staples of today’s repertoire. Bruno Walter noted ‘the magic of Rosé’s orchestra solos, particularly the sublime beauty of his violin solo in the Third Act of Tristan’. The violinist Otto Strasser wrote: ‘With its crystal-clear tone, sparing use of vibrato, and faultless intonation, his briefest orchestral solo had something personal about it which made the audience sit up and listen His influence on the whole string section was incredible. He had such a degree of authority that each of us gave our best, from the violins to the double-bases.’ He was also conscientious. Sir Adrian Boult recalled conducting a concert of British music at the 1935 Salzburg Festival, for which Rosé missed the first rehearsal because of his opera duties. ‘Next morning I happened to walk through the Mirabell garden when I heard a violin playing something familiar It was the first violin part of the first scene of Vaughan Williams’s Job When I went back a little later, sure enough, the solo violin (Elihu) scene was being carefully played and practised The most famous leader in Europe, having missed one rehearsal of an unfamiliar programme, felt he must put himself through the experience of playing every note of that programme (including the obviously slow and easy parts) before going to the second rehearsal.’ Rosé is unsympathetically portrayed in the memoirs of Alma Mahler and Flesch, though the latter gives a fair picture of him as a fiddler. It is often recalled that Rosé turned down Fritz Kreisler for a leading position in the Court Opera Orchestra with the comment ‘He’s no good at sight-reading’. Was this the action of an established player safeguarding his position against a potential rival? Or did Rosé find Kreisler’s sound, with its continuous vibrato which was soon to revolutionise string playing, too individual and outlandish? Listening to Rosé’s very nineteenth-century sound, with its economic application of vibrato, predisposes one to the latter view. The final verdict on the incident must be that it did both the young man and the world a favour, by forcing the indolent Kreisler into a solo career. And it should be stressed that when the brilliant young Adolf Busch turned up in Vienna in 1912, Rosé gave him every encouragement, playing the Bach Double with him, conducting when he played concertos, presenting a string duo recital with him and even planning a joint concert by their quartets (which alas had to be cancelled). Above all, Rosé deserves to be known as a quartet leader, one of the greatest in Vienna’s history. As the hub of an empire, the Austrian capital could call on several national traditions of string playing, principally the Czech and Hungarian, and from this melting pot emerged a distinctive Viennese school which expressed itself equally well in light and serious music. The world’s first really significant quartet was that led by Ignaz Schauppanzigh in Vienna, and the city boasted many fine ensembles over the years, though few acquired international reputations. Rosé’s was one of the exceptions and toured quite widely, considering that all the members retained their orchestral jobs. In 1928 it even visited America. Six or eight subscription concerts were given in Vienna each season, drawing capacity audiences. Among the composers whose works the group premièred were Karl Goldmark, Robert Fuchs, Hans Pfitzner, Ewald Strässer, Karl Weigl, Hans Gál, Hugo Kauder, Franz Schmidt, Emil von Reznicek and Erich Korngold. The greatest rumpuses were caused by the first performances of Arnold Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht (1902) and first two quartets (1907-08). Rosé rehearsed the First Quartet meticulously, giving it some 40 sessions, but it met with antagonism which was exceeded only when the Second Quartet was given with Marie Gutheil-Schoder as soprano soloist. The Rosé players also took part in the première of the First Chamber Symphony, with no greater success. No wonder they made little effort to export Schoenberg’s music, although they took new works with them to most countries. Since the Viennese pool of musicians was small, there was a good deal of ‘promiscuity’: even the Rosé Quartet was not immune from the poaching and swopping of players, and it had many changes in more than six decades of existence. By the time the quartet movements on this disc were recorded, the ensemble was quite well settled. Second violinist Paul Fischer had been in place since 1905 and violist Anton Ruzitska since 1901 (anyone who thinks Rosé was a heartless manipulator should know that he kept Ruzitska in the ensemble for some years after the player developed Parkinson’s disease). The most recent recruit was cellist Anton Walter, who joined in 1921. Over the years the quartet appeared in concert with many composers and such pianists as Xaver Scharwenka, Annette Essipov, Alfred Grünfeld, Julius Röntgen, James Kwast, Arthur Friedheim, Ferdinand Löwe and Carl Friedberg. |