- Profession: Critic Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung 1897-1905

- Residences:

- Relation to Mahler: Important link and intermediary between Mahler and the Wagner family. A fervent Wagnerian and close friend to Cosima Wagner (1837-1930) and Siegfried Wagner (1869-1930), and at the same time an objective, honest critic who recognized Mahler’s merits and maintained friendly if not close relations with him. It was Gustav Schonach who described the 11-1899 revival of Die Meistersinger to Cosima in glowing terms and introduced her to write to Mahler a year later. Schonaich new Mahler well in Vienna. Visited until his death in 1900 1907 Hotel Imperial. Mentioned by Natalie Bauer-Lechner (1858-1921) in her recollections. Wrote review of Tonkunstlerversammlung des ADM (1905) in Graz with 1905 Concert Graz 01-06-1905 – Des Knaben Wunderhorn, Kindertotenlieder, Ruckert-Lieder.

- Correspondence with Mahler:

- Born: 24-11-1840 Vienna, Austria. Gustav Karl Franz Xavier Schönaich (Also: Schönaich, Schoenaich, GS, G.S.). Never married.

- Addresses:

- 1860 – Seilerstätte 32

- 1875 – Schottengasse 11

- 1876 – Wipplinger Strasse 20

- 1880 – Kärntner Strasse 31

- 1900 – Opernring 3

- 1901 – Krugerstrasse 1

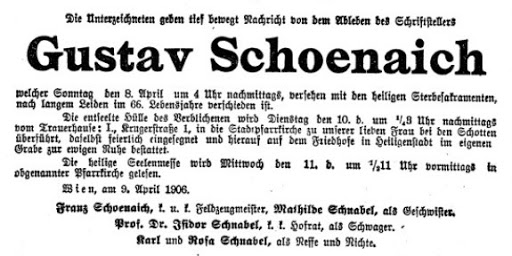

- Died: 08-04-1906 Vienna, Austria. Aged 66.

- Buried: 10-04-1906 Funeral Mass in the parish Church of Our Lady of the Scots, Herrengasse, Vienna. Heiligenstadt cemetery. Grave A-2-69.

After visiting the Piaristengymn from 1859-1863 studied Law at the University of Vienna. After legal practice, he joined the Austrian Boden Creditanstalt in 1869, where he worked from 1871 as a beneficiary, from 1873 as a civil servant and from 1878 as an adjunct, and to which he was a member until the mid-1980s.

Through his stepfather, the doctor and music lover Josef Standthartner, whom his mother married in 1856, he soon found direct access to the Vienna musical life. From an early age, he owned a select group of friends (which also included Richard Wagner and Peter Cornelius) and was one of Hugo Wolf (1860-1903)‘s early supporters in Vienna. He had a lifelong friendship with Felix Mottl (1856-1911).

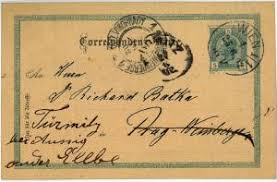

25-06-1902. Letter by Gustav Schonaich (1840-1906) to Richard Batka (1868-1922) (1/2)

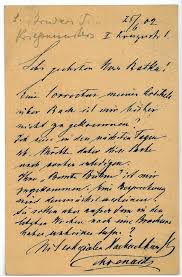

25-06-1902. Letter by Gustav Schonaich (1840-1906) to Richard Batka (1868-1922) (2/2)

He wrote for the “Österreichische Constitutionelle Zeitung”, the “Debatte” and the “Österreichische Revue” for the “Neue Wiener Tagblatt” (1892-1896), the “Extrapost” (1894-1895), the “Neue musical press” (1895-1896), the “Reichswehr ” (1896-1897), the “Wiener Rundschau “(1897) and the “Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung” (1897-1905).

He wrote a large number of reviews, reviews and features about various cultural events. His contemporaries valued his tolerance and education as well as his sophisticated, witty style. Well-known personality in Vienna.

Silhouette by Otto Bohler (1847-1913). Titled “Dancing Vienna”. Mahler is shown dancing on the left. The other dancers include the actor Georg Reimers (middle) and the critic Gustav Schonaich (1840-1906) (right).

09-04-1906. Obituary Gustav Schonaich (1840-1906).

Reviews

Gustav Schonaich (1840-1900) about Gustav Mahler (1860-1911).

- Gustav Mahler

- Symphony No. 3 (1904)

- Symphony No. 5 (1905)

- Selma Kurz (1874-1933) (1904)

- Das Rheingold (02-1905)

- Das Was Ich (03-1905)

- Die Rose vom Liebesgarten (04-1905)

- Le Donne Curiose (06-1905)

- Feuersnot (06-1905)

- Fidelio (08-1904)

- Don Giovanni (12-1905)

- Die Entfuhrung (12-1905)

- The Marriage of Figaro (12-1905)

Henry-Louis de La Grange

Henry-Louis de La Grange (1924-2017) about Gustav Schonaich (1840-1906) in his Vol. 2. Vienna: The Years of Challenge (1897-1904).

pp. 79-80 [1897]: “Anna von Mildenburg had finally been invited to sing at the Vienna Opera in December….

“Mildenburg’s guest performances started on December 8 with Die Walküre, which Richter conducted, and continued with Lohengrin on 14 December, and Fidelio, again conducted by Richter, on 17 December….Gustav Schönaich, in the Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, praised Mildenburg’s dramatic temperament and intelligent acting; her engagement would fill an important gap in the Vienna ensemble, which at the moment possessed only one dramatic soprano.*

*Schönaich, the most devoted ‘Wagnerite’ of all the Viennese critics, noted that the ‘joyous’ interpretation of Brünnhilde’s cry was completely new, even contrary to tradition. Gustave Schönaich (1840-1906) was the son of [Franz Schönaich,] a court official who had been the Austrian Minister of Education, and whose death had left him an ophan at an early age. Frau Schönaich subsequently married a famous doctor, Dr. Standhartner, director of the largest hospital in Vienna. She received in her salon the principal artists and greatest musicians of the time. Schönaich studied law at the Univ. of Vienna and for some years held the post of legal consultant to the Bodenkreditanstalt. He was 34 before he became a writer and critic. He first joined the Wiener Tagblatt, then the Die Reichswehr, and finally the Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, of which he was now editor-in-chief. A friend and intimate of Wagner until the latter’s death, he remained close to the Wagner family and regularly visited them at Bayreuth, so that he came to be regarded as their semi-official spokesman in Vienna. He was renowned for his wit, culture, and conversational gifts as well as his gourmandise and corpulence. He died of heart disease in 1906.”

pp. 114-115 [1898]: “According to Heuberger, ‘an unprecedented suspense’ held the audience spellbound during the whole performance of Götterdämmerung….

…

“After some hesitation Mahler suppressed the rope in the Norn scene, using a real rope for rehearsals and then removing it at the last moment. So the Norns only mimed throwing the rope in the air and catching it, and the fact that there was no rope was hardly noticed. He nevertheless received a letter of protest from Cosima Wagner, to which he replied that he had taken this step ‘at the dictates of his conscience as an artist and man of the theatre’. Gustav Schönaich, who dined frequently with Mahler and Natalie, brought the matter up again on behalf of the Wagner family. ‘Spare yourself this trouble, I beg you!’ replied Mahler.”

p. 123 [1898]: “For Gustav Schönaich, Mahler’s conducting of the [Mozart] Symphony No. 40 was ‘beyond all praise’. ‘Never had one been more blissfully aware of the winged, light genius of this masterpiece. A spirit of grace and delicacy breathed through the performance.'”

p. 204 [1900]: “Robert Hirschfeld hailed Mahler’s version of the [Beethoven] Fifth Symphony as ‘moving by its very novelty’, for the conductor saw in Beethoven not the ultimate perfection of classical development, but a ‘mighty prophet of the new style in music’. At this time Hirschfeld was prepared to accept most of the instrumental retouching,* except for the audacious doubling of the bassoons in the Finale, which he regarde as ‘intolerable and contrary to the nature of Beethoven’s music’. Schönaich was also opposed to this** and certain other ‘surprising ans unusual’ features, such as the fast pace of the first movement*** and the slowness of the next two.**** He conceded that the ‘triumphal jubilation’ of the Finale, with its ‘noble pride and blinding brilliance’, was ’eminently typical of Beethoven’. In another article in the Wiener Tagblatt, the same critic, in a more liberal mood, declared that it was ridiculous to be put off by the new tempos, even if they were contrary to tradition, and to refuse to recognize Mahler’s feeling for Beethoven’s ‘grand style’. His powerful accentuation, his imposing crescendos, and the radiance of the final hymn of victory indeed revealed ‘a magnificently talented conductor, who is entirely familiar with the work’.

*Particularly the use of a piccolo in the Finale. However, he objected to the muting of the horns at the beginning of the Scherzo and the doubling of the bassoons by the horns in the Finale: although he had tried to subdue their tone, Mahler had in fact altered their actual sound…. Schönaich, on the other hand, claimed that such doubling was ‘accepted by all the famous conductors in Germany’.

**According to Karpath [Lachende Musiker (München, Germany: Knorr & Hirth, 1929)], Schönaich always opposed Mahler’s instrumental changes because he was afraid that Vienna would regard him as a ‘desecrator of Beethoven’.

***Wagner and Bülow had played it slower, he claimed.

****In his view, the slow tempo of the Scherzo had had ‘particularly curious’ results in the famous double-bass passage in the Trio.”

p. 230 [1900]: “However, when Gustav Schönaich wrote that nothing remained in these compositions [of Lieder] either of Knaben or of Wunderhorn’, Mahler was hurt, since Schönaich had always professed to admire him whole-heartedly and had, so to speak, been raised and educated (heranwuchs) in Bayreuth.”

p. 288 [1900]: “Fifteen months later, Mahler again conducted The Magic Flute. … Gustav Schönaich [in the Wiener Allgeneine Zeitiung (27 Nov. 1900] found the casting perfect, particularly Gutheil-Schoder, who was making her début as Pamina:

“Her appearance recalls an antique figure by Raphael. Her singing and acting go together, intermingled in chaste sweetness. All was artistically felt and interpreted, yet without a shadow of exaggeration in the subtleties of the dynamics. To give just one example: when Serasto, appearing unexpectedly, terrorizes Papageno and Pamina who are attempting to escape, Papageno asks, ‘But what shall we tell him?’ and Pamina replies, ‘The truth, even if a crime!’ The established custom has been that Pamina declaimed these words in accents of heroic determination. With Frau Schroder, on the contrary, there is an inimitable mixture of embarrassment and slight, affectionate reproach aimed at Papageno, as if the very idea of telling anything other than the truth were being suggested to her for the first time in her life. A stroke of genius, not isolated either, and for me, at least, a handsome recompense for the lack of softness in the middle register of her voice.”

p. 309 [1900]: “Even Gustav Schönaich, who until then had shown considerable fairness in his assessment of Mahler, and had found his Second Symphony ‘pleasing and intensely personal’, could perceive no links between the movements of the First and declared the ‘tome structure’ completely irrational. “Is it a weasel, a cloud or a camel?’ he asked, paraphrasing Shakespeare [Hamlet, iii ii, 390-400]. The ‘auditory pleasures’ had irritated him as much as the dissonances, for all had seemed equally unmotivated. Mahler had been a master of orchestration sixteen years before, but his personality had still not asserted itself. Recalling that Wagner had feared that Berlioz would end up being ‘buried beneath his own orchestral machinery’, Schönaich remarked that Mahler had also succumbed to the hazardous joys of using a hitherto unprecedented orchestral language, and that, without fully realizing it, he had attached more importance to ‘the glittering outer garment of the thought than to the thought itself’. Moreover, his humour merely grated, for ‘Callot’s manner was unsuited to music. It was impossible to discern the slightest link between the catasphrophic fourth movement and the rest. Mahler should never have risked his reputation as a composer by performing such a work.”

pp. 31i8-319 [1901]: “Carried away by his enthusiasm for this labour of re-creation [a new production of Wagner’s opera Rienzi], he dumbfounded one of the Viennese critics by asking ‘whether he didn’t agree that Rienzi was Wagner’s most beautiful opera and the greatest musical drama ever composed’. The unidentified critic may have been Schönaich for, according to Max Graf, he had long since noticed this peculiar trait in Mahler’s character: “I’ll tell you what your enthusiasm reminds me of,’ he said to Mahler one day in the Café Impérial, ‘foie gras’. Mahler asked him what he meant, and Schönaich replied, ‘Because geese are force-fed until they develop a liver disease which produces the succulent foie gras. You, when you prepare a new production, stuff youself with enthusiasm and this results in a marvellous performance.’ Thereafter, when staging an opera that required a great deal of effort, Mahler would often announce, ‘the foie gras will soon be ready’, and later on, when the critics began to attack each of his innovations, ‘die Herren Vorgesetzten once again consider it a liver disease….But we think the foie gras will be excellent!'”

p. 715 [1904]: “In an obituary [for Eduard Hanslick] whose tone alternated between the strongest criticism (notably concerning Hanslick’s hostility towards Wagner) and respectful admiration, Schönaich acknowledged that Hanslick ‘never wrote a boring article’ during his sixty-year career.”

—-

A Vienese critic on Gustav Mahler’s youthful work:

“A harmonic effect that is a real stroke of genius is the seven-part choral entry m part one over the sixteen-bar-long pedal point on F ( O Spielmann). Mahler’s music never fails to make a significant impression when it succeeds in keeping itself within bounds. But when he composes ‘a joyful noise’, it’s a corybantic hubbub….”

Gustav Schönaich, Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, 20 February 1901.

—

A Vienese critic’s review of stage designer Alfred Roller’s first operatic première, “Tristan und Isolde“:

“There would of course be no point in insisting on eternally imitating the decor of the first Tristan. Sets and decor at the time the work was written were still a matter of craft, not art. It was not until 1876, for the decor of The Ring, that Wagner found in Joseph Hoffmann an artist whose imagination and great technical skill overcame these enormously difficult problems. The design for Tristan must aim for much more intimate and subtle effects, as befits the subject. Professor Roller, who knows Wagner’s works intimately, has judged these effects and realized them with the finest artistic sense. The idea of having the ship come on to the stage diagonally proved to be entirely felicitous. It made possible a splendid play of light on the sea, which was now visible to the audience over the side of the ship. The raising and lowering of the curtain and the sail produced extremely felicitous colour-contrasts. The over-all coloration, determined by the richly nuanced orange of the dominant sail, satisfied the eye without distracting it from events on stage. The intentions which underlie the decor of the second act are extremely ingenious and derive from an intimate understanding of the mysterious interplay of allusions within the text: ‘In darknes you – but I in light.’ The poetic opposition of Day and Night which dominates this scene is reflected by the setting. The bare wall of the royal castle reflects white moonlight, while the bench on to which the two lovers sink is plunged in darkness. This has certain disadvantages. The darkness hides the expressions of the lovers, and the rostrum surrounded by bushes conceals Isolde’s first entry: here she slips out of a little side gate instead of appearing as usual, very effectively, framed in a huge castle portal. The third act is a work of decorative art. The whole stage is bleak and desolate. The mighty lime-tree, among whose roots Tristan lies, the hill upon which Tristan dies, and against which the expiring Isolde so gloriously stands out, bear witness that a man with a true vocation has here put himself at the service of the work.”

G.S. (Gustav Schonaich), Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, 25 February 1903 (“The premiere took place on 21 February; Mahler conducted; Anna von Mildenburg and Erik Schmedes sang the title roles. Schönaich, who had known Wagner personally, was considered to be the Wagner specialist among the Viennese music critics.” p. 167. Kurt Blaukopf and Herta Blaukopf, Mahler: His Life, Work & World. (London: Thames & Hudson, 1991)